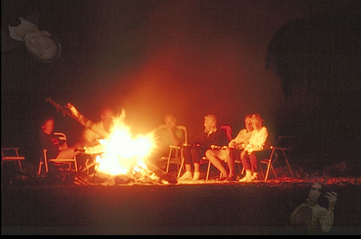

You're seated at a fire with as many as eight or nine other people. You're scared, you're restless, you're tired. At your feet, and within easy reach, each of you has a weapon: sticks with crudely-hafted stone blades, or sharp hand-axes with serrated edges.

Behind you, beyond the furthest reaches of the light, monsters slide through the darkness. Picture fangs the length of your fingers, claws like knives; they're as quick as regret and as quiet as cold. Only the fire keeps them from dashing in and snatching you away at will. You try to forget they're there and enjoy yourself, but sometimes you catch brief glimpses of oval eyes glittering in the light.

To find out your fate, turn 600,000 pages to the future.

The people in this scenario didn't really have much of a choice, because this isn't fiction, this is history. This is the beginning of culture, the beginning of what makes us human. This is page one, the beginning of you.

Our ancestors gathered around campfires like these nightly, while real monsters watched. Back then, claws and fangs didn't fear us like they do today. We were soft and slow and blind at night. So why should they?

The other day I was asked to give a quick blurb about stories. Stories: what are they? Having degrees in English and Anthropology, I'm always like that guy who only has a hammer: to him, everything looks like a nail -- ask me a question and all my answers come back 'caveman.'

(Okay, not 'cave man,' that's an outdated and always-has-been inaccurate term, but you know what I mean.)

Because, hey, the answers for most questions do involve cavemen if you wish to be properly thorough. So what if 600,000 years have passed since the campfire. Inside we're still the same. Except now we have more stuff.

While we were making all our great stuff, concurrently we were sculpting ourselves through our stories, and this process began in the safety and comfort of the flickering firelight, the birthplace of all culture.

Because any of the people sitting there in the light who didn't physically have the propensity for storytelling, or for listening to stories, probably wouldn't be your neighbor, or anyone's neighbor, much longer.

Scenario within the scenario: Bob the Caveman was out that day and ran into a spot of trouble. In fact Bob was attacked by a gyro-slug, the huge imaginary prehistoric slug the size of a bear. Ferocious, were gyro-slugs, famous for having two spinning antennae atop their heads which they would use to commit acts of unparalleled aerial predation upon poor bipedalists stuck to the ground by their feet.

Page one is a strange and scary place.

Normally, meeting a gyro-slug would mean certain death for poor Bob, but this day Bob evades its first assault, the slug crashes to the ground, and quite by sheer dumb luck, lands near the salt lick which Bob had been quarrying, and melts with many unpleasant raspberry noises into a pile of gyro-slug mush.

Bob is ecstatic, and fortunately for everybody around the fire, Bob is a good storyteller. He arranges his thoughts about the incident in an orderly and rational fashion, using compelling details about the event, and is skillful at providing emotional cues about how he felt at the time to which his audience can relate. Finally, he brings the tale to a satisfying crescendo. Everybody sighs. Denouement. Good ol' Bob. What would we do without him. For a few moments, the monsters sliding through the darkness are forgotten.

Here's where I need another graphic: WHERE I ACTUALLY REALLY, REALLY COME TO A POINT.

Half the people around the campfire don't have the physical propensity for storytelling, or for the rational organization of information that Bob possesses. But just for the sake of simplifying a ridiculous scenario, let's say that one of them is very, very poor at it, even while being wonderfully bright in every other respect. From Bob's story he fails to take away -- with any serious retention -- the location of where Bob was attacked, where Bob found salt, or how he evaded certain death. The rest of the group begins carrying salt with them wherever they go. When attacked by gyro-slugs in the future, suddenly they are the victors, until the terrible squishy predators learn to fear humans.

But not before they fall upon our hapless outlier -- saltless -- and lacking the genetic predisposition for storytelling, removing him from the gene pool.

This example is a bit extreme, of course -- Gyro Slugs were only two-thirds the size of what I've described -- but, in essence, the propensity for storytelling allows for the greater diffusion and retention of facts and ideas. Those with the best ideas and communication skills were the best suited to survive and pass on their life-saving storytelling acuity to successive generations.

Especially since what our unlucky outlier lacked most from that fireside meeting was the sense of growing closeness and comaraderie with the rest of the band, the buddings of cultural identity, without which, we could hardly call ourselves human.

And if you question in your mind whether unconscious keys like this really could have been passed down through the ages, ask yourself why people have an intrinsic fear of the dark, or why so many find fire so immediately comforting.

A mere 600,000 pages later, we still crave stories that involve danger, triumph, and reward, even though we no longer have to face these things on a daily basis. Now we crave them because we love them.

So, tonight, as I Lord of the Rings myself to sleep, I'll take a moment to remember page one and my predecessors who listened.

And I'll remember to bring a small bit of salt in my pockets tomorrow when I go to the store.

Just in case.